|

|

Cardiff: Historical Notes

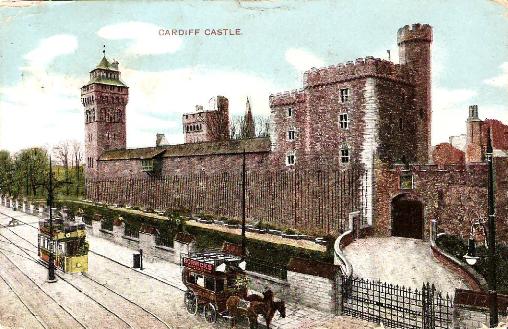

Cardiff Castle - card posted in 1911

'The Normans came in from the sea and coal came down from the hills. The coal made even more money than the Normans, and a gaggle of cottages around a huge castle became a city which has at last managed to get itself recognised as the capital of Wales.' (Gwyn Thomas, 1964:135).

Cardiff (Caerdydd in Welsh) is situated in the ancient cantref (hundred) of Cibwr in the former county of Glamorgan. In 1801 it was a small town with a population of just 1870, but by 1859 it had grown to 36,000 and 85,378 by 1881. The Romans had a coastal fort in Cardiff as early as AD50, with a much larger structure built around AD260 along similar lines to the Saxon Shore forts on the South and East coasts of Britain (Mattingly, 2007). Based on the Roman fort (caer names in Welsh indicate Roman fortifications), the town was the centre of power of the Welsh prince Morgan ap Hywel ap Rhys around 900 AD. It was subsequently destroyed and then rebuilt by Iestyn ap Gwrgant, the last native prince of Morgannwg, in 1080. After employing Robert Fitzhamon and other Norman soldiers in a dispute with Rhys ap Tewdwr, Iestyn was overthrown by Fitzhamon. Fitzhamon replaced the wooden Welsh castle with a stone version, some of which remains in the castle rebuilt by by the Marquesses of Bute betwee the 18th and 20th centuries.

The Marquesses of Bute were responsible for much of the development of Cardiff as a major port in mid-Victorian times. In 1859, for example, the docks exported 1,490,312 tons of coal, 195,961 tons of iron and 16,339 tons of coke. 12 years later, in 1871, the port exported 177,711 tons of coal on 321 ships in March alone. American consul Wirt Sikes (1881:5-5) described Cardiff:

'Cardiff, the handsome sea-port town which sits at the mouth of the Taff, does not owe its importance to the ancient ruins which besprinkle Glamorganshire, but to the fact that the county is the greatest coal centre of the British Empire. To iron and coal Great Britain chiefly ascribes its grandeur among nations, and from Glamorganshire it draws vast quantities of these; the deposist are deemed well-nigh inexhaustible. Cardiff is but an outlet for this wealth, and is not, as some suppose, a smoky and sooty sort of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. It is clean, handsome, with broad streets and fine edifices, and a clear blue sky overhead. From the collieries and iron-works of the mountain towns on the Taff by railway and canal the mineral treasures of Glamorganshire are brought down to Cardiff and shipped opon salt-water. As regards its relations with American shipping; Cardiff is the second sea-port town in Great Britain, the first being Liverpool. A greater number of American ships yearly arrive at and sail from Cardiff than from London. It is only within the the last forty years that Cardiff has assumed this importance, and it is barely a hundred years - a bagatelle in the history of Cardiff, though a somewhat important period of time in American eyes - since it was a small town, with no better means of communication with the mining-regions than donkey-power. It was customary for women and boys to drive into port mules laden with coal in bags, and iron came down the hills in scanty wagon-loads.'

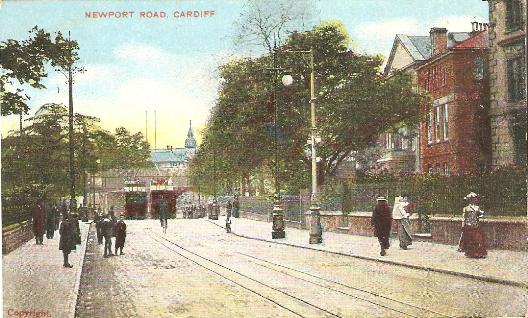

Newport Road, Cardiff - vintage postcard

Stage-coaches

Marie Trevelyan (1893:53-4) wrote:

'Stage-coaches ran from country places into towns, and many of thse vehicles were to be seen in Cardiff on Saturdays, and sometimes on Mondays, until twenty-five years ago. They were well known. There were Pob-joy's 'bus, that ran between Newport and Cardiff, twelve miles; Macey's 'bus, that plied between Llantwit Major and Cardiff, a distance of eighteen miles; and in addition to these were the 'busses from Pontypridd, Llantrisant, Treforest, and other places. The last of the old 'busses going into Cardiff were Pob-joy's and Macey's.

'Then there were the carriers who conveyed heavy goods to and from the towns before the trains came. The last of these old carriers was known as Robin o'Roos.

'The 'busses were supplanted but not superseded, so far as shelter is concerned, by the modern brake or waggonette. Even now from many remote districts, carriers convey passengers and goods to the large towns. On Saturdays, and from some neighbourhoods on Mondays, these carriers are to be seen on the highways of Wales. All kinds of vehicles are called into requisition. There are market-cars, each capable of being crowded with six persons, heavily-laden wagogons, washed and unwashed waggonettes, and brakes with well-groomed or totally ungroomed horses.

'Some of these vehicles toil slowly along for many hours. The drivers and passengers alike appear to be perfectly contented with the pace at which they travel, and it is by no means unusual to hear exclamations against a quickened rate of locomotion. These "slow coaches" trundle on through the dust and heat of summer, and the cold and darkness of winter, halting at every wayside inn where the driver and passengers alight, to refresh themselves with copious draughts of cwrw da, "good ale", or ale and ginger beer, or to warm their feet and fingers, and have a "drop of something short (spirits) or gin hot". '

The City Centre

Noting that South Walians are proud of Cardiff's city centre, Gwyn Thomas (1964:140) observes:

'In the city's centre is a patch of noble amenity in marble and granite. Wealth did not come too long before civic pride here, and there is an Athenian grace about the group of buildings, the County and City Halls, the Museum, the Law Courts, that extend the castle's dignity on the city's northern side. Among the buildings are bits of memorial statuary. To the artist they bring no comfort, and to the social historian they are odd. The men remembered were, without doubt, wise, brave or rich, but a broze frock coat, considered as deathless art, does not even get started.'

As for the castle itself, Thomas considers that the 'steady residence of the Butes in this pile has given it a lived-in, manorial touch' - even if it now belongs to the City Corporation.

'The rebuilt section of the castle, through which tourists are conducted in gasping groups (astonishment and stairs activate the gasps), is a nineteenth-century flourish of triumphant wealth. The Chaucer room, a bed-chamber with a conical ceiling made up of illustrations in coloured glass of Chaucer's tales, in which some privileged insomniac might well have dropped off while counting Canterbury lambs. There is a room designed to reproduce the reclining chamber of a harem which always causes a thoughtful pursing of lips among the more dour puritans from the hills.'

References

Mattingly, David (2007) An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, 54 BC - AD 409 (The Penguin History of Britain), Penguin.

Sikes, Wirt (1881) Rambles and Studies in Old South Wales, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington.

Thomas, Gwyn (1964) A Welsh Eye, Hutchinson.

Trevelyan, Marie (1893) Glimpses of Welsh Life & Character, John Hogg.

Copyright © 2009-2025 Alan Price and IslandGuide.co.uk contributors. All rights reserved. Island Guide makes minimal use of cookies, including some placed to facilitate features such as Google Search. By continuing to use the site you are agreeing to the use of cookies. Learn more here